Debt, a Risk for Sovereignty and Cohesion in France

Debt, a Risk for Sovereignty and Cohesion in France

Nicolas Marques // 21 July 2025

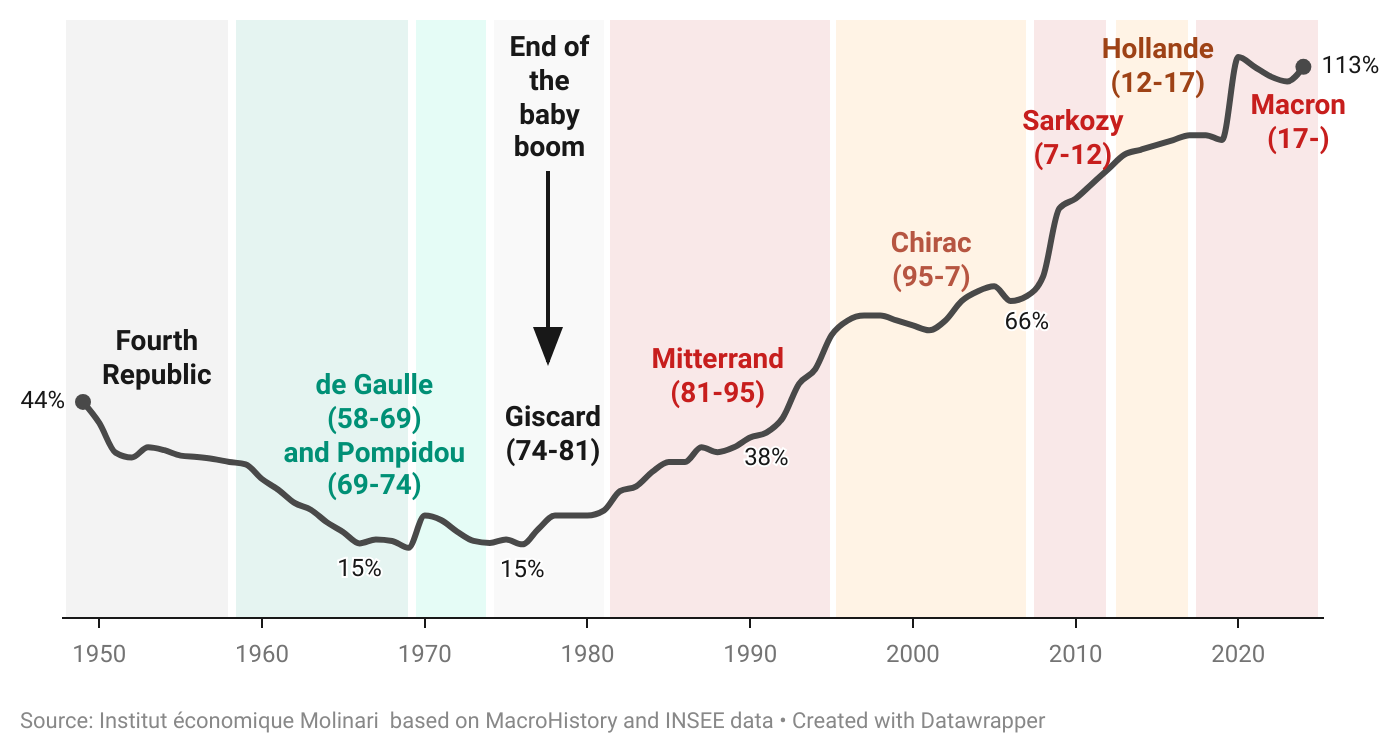

At the end of 2024, French general government debt stood at 113% of the country’s GDP, or approximately €50,000 per capita. Since 1969, the debt-to-GDP ratio has increased eightfold.

Many have forgotten that, at the end of the ‘thirty glorious years’, France’s public finances were among the healthiest in Europe. This was due to the reorganisation orchestrated by General de Gaulle. The Pinay-Rueff plans of 1958 (which aimed for a return to equilibrium) and the Rueff-Armand of 1960 (in preparation for the European common market) amplified the effects of post-war demographic and economic growth. In 1969, when General de Gaulle resigned, public debt was no longer an issue, standing at only 15% of GDP. Under the presidencies of Charles de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, and then Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, the budget was in surplus 70% of the time, a performance unseen since the period from 1895 to 1913.

The evolution of public debt in France as a percentage of GDP from 1949–2024

In 1980, France was still a well-managed country, with debt representing just 21% of GDP. However, since then, the accounts have never been balanced, and public finances have drifted out of control. Initially, this was due to the left’s rise to power, which led to a proliferation of costly measures, such as nationalisations, reduced working hours, and the lowering of the retirement age to 60. These measures resulted in a tripling of public debt, from €5,800 per capita to €19,300 per capita. During François Mitterrand’s two terms in office, public debt as a proportion of GDP rose by 6.6% per year, twice the rate seen under any subsequent president (2.7% a year).

The uninterrupted rise in public debt, beyond risky political choices, also stems from the end of the baby boom – a demographic phase that had been favourable to public policies aimed at financing high levels of social protection through labour taxes. In France, pensions account for 25% of public spending. Furthermore, 45% of the increase in public spending since the end of the baby boom can be attributed to pensions, which are almost exclusively financed through contributions from the working population on a pay-as-you-go basis or through taxation. Pensions represent a debt to current and future pensioners amounting to about 400% of GDP. This commitment, equivalent to €175,000 per inhabitant, is not included in the official calculation of public debt, as pension promises are not legally binding and can be revised downwards.

The cost of visible debt has been contained thanks to negative interest rates over the past several years. However, this is becoming less and less the case. By 2024, the cost of this debt will amount to €63 billion, or 2.2% of GDP, almost as much as the cost of state employee pensions (€66 billion, or 2.3% of GDP). Together, these two debts, explicit and implicit, account for three-quarters of the public deficit in 2024, which is expected to reach €170 billion, or 5.8% of GDP.

So far, this fragile house of cards is holding up. Financial institutions need public debt, and French debt remains a sought-after product. However, excessive debt has deleterious effects. In particular, it sterilises the savings of the French population, as these savings are used to finance daily spending and are not available to finance long-term investments necessary for maintaining wealth creation. This is why France, and Europe as a whole, has fallen behind the rest of the world in terms of growth and innovation.

De Gaulle rightly considered that ‘We cannot have an independent policy and an independent defence if we do not have an independent economy and sound finances. This is the sine qua non of national independence.’ Fifty-five years after his death, at a time when debt has increased eightfold, these words are more relevant than ever. Excessive public debt that is not sufficiently productive is much more than just a financial issue; it is a sword of Damocles for France, posing a risk to its sovereignty and social cohesion.

This is a translation of 'La dette, un risque pour la souveraineté et la cohésion'. You can read the original version by clicking here.

Nicolas Marques is the Director General at Institute Économique Molinari.

EPICENTER publications and contributions from our member think tanks are designed to promote the discussion of economic issues and the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. As with all EPICENTER publications, the views expressed here are those of the author and not EPICENTER or its member think tanks (which have no corporate view).